STREET ART UNDER SUPERVISION. THE EXPERIENCE OF UKRAINIAN MONUMENTALISTS

We meet Alla Horska's granddaughter, Olena Zaretska, near the "Wind" panel, which her grandmother created sixty years ago. At that time, a several-meter mosaic of glass and smalt pieces decorated the facade of the fashionable restaurant "Vitryak". Now the establishment is no longer operating, and the building itself is drowned among skyscrapers. The panel, which combined motifs of Ukrainian folk art and avant-garde, has peeled off and looks frankly neglected. Zaretska says that they created a petition for reconstruction, because "Wind" is the only monumental work of her grandmother left in Kyiv. Most of the works of Horska and her group (which included Viktor Zaretsky, Boris Plaksiy, Hryhoriy Synytsia, Anatoliy Limaev and Boris Smirnov) were created in eastern Ukraine. The thing is that in the capital, ideological overseers tightened the screws, and Donbas was open to monumental art - come and work. And they took advantage of this opportunity.

"Contemporaries called Gorska the wind of change. She understood perfectly well that monumental art is a tool of propaganda and that forbidden ideas can be promoted through it. Therefore, in her work, she concentrated on monumentalism, as if she felt that she needed to leave as much legacy as possible."

·

Olena Zaretska and Alla Gorskaya's panel "Wind"

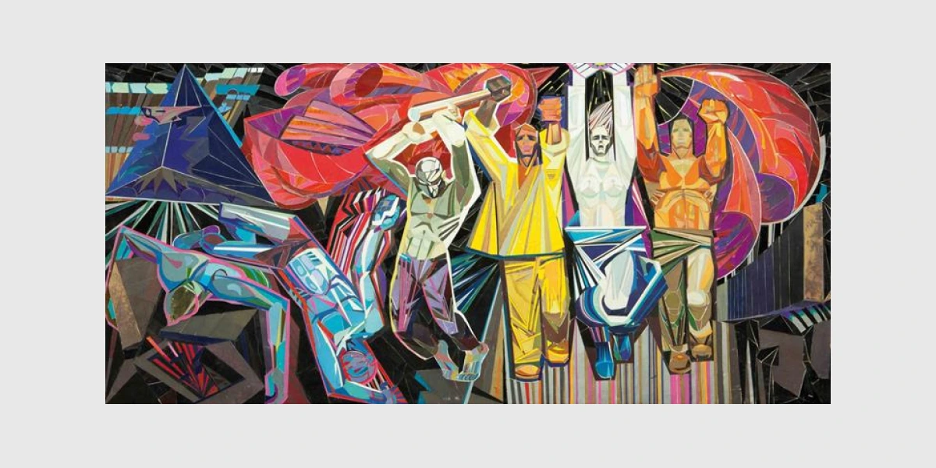

Creating mosaics on the mining theme "Coal Flower" or "Prometheus", Gorska's group managed to secretly promote the national color, decorating the drawings with sunflower flowers or using yellow and blue colors. At the stage of submitting and approving the sketches, it was not easy - there were art councils that, like Stalin's troikas, decided whether to take this work or give money for its execution.

Mosaic by Alla Gorskaya and Viktor Zaretsky "Tree of Life"

For example, there was a complaint about the mosaic "Tree of Life" - the plant is depicted with roots, which hints at its Ukrainian origin, and this contradicts the socialist vision, which envisaged the creation of generalized Soviet images without an emphasis on national self-identity. We had to get around it and come up with the idea that it is the roots of the tree that resemble a mining blast furnace.

“It was always difficult to get through this art show, there is a known case when they did not let in a stained glass window with the image of the poet Shevchenko, because it “does not correspond to the image of a Soviet person”. But he was never a Soviet person! Gorska lacked diplomacy during such discussions, she would explode, shout, disagree, and she had to have a completely different behavior, not so eccentric, not so sincere, direct. Usually, other team members were sent to the negotiations. And they managed to agree on compromises. If you look closely, the mosaic “Victory Banner” is not decorated with any Soviet symbol — no hammers and sickles,” Olena Zaretska reflects.

"Banner of Victory"

Thanks to compromises, bright panels with elements of Hutsul embroidery or painted Easter eggs appeared on the walls of Donbas schools, reminding the indigenous Ukrainian population and visitors from other republics of the region's Ukrainian identity. These were bright spots in the gray everyday life of miners. At the same time, the artists of the sixties were constantly intimidated, tried to break them, and their close friends were in camps. The authorities meticulously uprooted the sprouts of dissent. Demands for broader public, religious, and national rights, even from a small circle of people, were considered anti-state activities, because individual dissenting citizens could sow doubts about the authorities among the entire population. Dissidents were isolated from society, thrown into prisons and psychiatric hospitals. But this did not stop the artistic movement of resistance, but on the contrary, strengthened it.

Horska emphasized that monumental art is a sea of "I," as if artists could be devoid of individuality, but together they would leave their mark.

Perhaps this was a consequence of collective thinking imposed by the Soviet authorities? However, when in 1968 the artist signed the "Letter of 139" - an open letter against the repression of Ukrainian artists, and as a punishment her name was struck off the list of designers of the "Young Guard" museum, she was upset. "They deprived me of authorship, they took away my name," she complained in a letter to her friend Stepan Zalyvakha, who was in exile.

Soon, Gorska will be deprived of her life - by organizing her murder, disguised as a family conflict. The legacy of the dissident artist, who lived only forty years, was also tried to cover with a black blanket of oblivion. Donbas mosaics began to be built over under the guise of building renovation. This is what happened with the phantasmagoric works "Boryviter" and "Tree of Life" in Mariupol. The panel was miraculously found when the building was being reconstructed, and the works were restored. However, at the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Russian troops into Ukraine, a shell hit the found mosaics, and now a huge hole gapes in the wall between them. Mariupol is occupied, and no one cares about the fate of the artistic creations.

"I'm afraid that the invaders will renovate everything and try to steal Gorskaya, turning her into a typical Soviet artist. It's scary to imagine how they can twist everything, because she, on the contrary, was against imperial views," worries Olena Zaretska.

"I was always afraid of a totalitarian system"

Kyiv resident Yevgenia Fullen leads a group of mural artists and has repeatedly been involved in high-profile scandals. She is accused of vandalizing historical buildings and even received an order to remove her mural. The mural is dedicated to France as a sign of gratitude for their military support of Ukraine. The building was planned to depict the characters of Victor Hugo's Notre Dame Cathedral - Quasimodo holding Esmeralda over a cliff, and next to them - a chimera.

Mural on Sichovyh Striltsiv

“We had permits, approval from neighbors, but some residents didn’t like the image of a chimera. Due to superstition, they believe it’s a bad sign: a Russian missile will fly into the house. People don’t understand that chimeras decorate Catholic cathedrals in Europe, there’s nothing wrong with that,” explains Yevgenia.

As a result, the city authorities remembered that the house was a historical monument and forced the authors to move the mural to another location, and the sketch was covered up with paint.

It was this “bizarre” incident that became the reason for organizing a commission in Kyiv to look after murals, because, according to its initiators, the capital is visually littered with low-quality works by monumental artists. It is now impossible to paint outdoors in the capital without official permission. Fullen suggests that the commission will approve only those works that fall within the framework of the unspoken “state trend” — to paint something patriotic, but not hyperrealistic, but abstract.

"Instead of giving artists the opportunity to advance, to be supported, we are regressing. I have always been afraid of a totalitarian system, repression, but I feel that we are heading towards this, the government is beginning to control creators, and it scares me."

"As for the commission, there are eight or nine people, among them there are muralists, obviously there is a conflict of interest. There is a whole list of documents that you have to collect, then come for a discussion, present them with a visualization of how the work looks, from the left, right, side, bottom. And then, perhaps, they will approve it. I do not exclude that we will have to give bribes. But we just want the city to have at least one less scribbled wall without unnecessary bureaucracy," explains Yevhenia Fullen.

Eugenia Fullen

The artist and her group focus on works with a social connotation - against domestic violence, with calls for the release of prisoners. They recently painted a fence on the territory of an orphanage and have already started decorating an animal shelter. Portrait works are also not bypassed - they created a mural in honor of the fallen soldier, Ukrainian hockey champion Oleksandr Khmil, the project was sponsored by his widow. But there was an embarrassment with the mural depicting the former commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine Valeriy Zaluzhny - they were ordered to move it. The image is on the wall of a boarding school for children with special mental needs and supposedly has a bad effect on them, because many people climb over the fence to take pictures of the mural. However, Fullen suspects that the real reason is different.

"These are already political games, they are turning a mural into a political tool, an agitation tool. For me, creativity is about self-affirmation, especially when we are now talking about a free country, where we should be free people. And they are trying to squeeze us into standards: you either cooperate or we are against you. You want to portray a person who saved the country, who prevented the Russian army from advancing, but you have no right to do so. Historical figures are a green light, and contemporaries are out of time."

Disagreement fee

“My father was a man of principle, he never compromised with the authorities, even when it had catastrophic consequences,” states the son of the famous artist from the sixties, Boris Plaksiy.

He meets me in an apartment in an ordinary high-rise building that looks more like a museum. In addition to the numerous paintings on the walls, the rooms and hallway are decorated with carved wooden furniture with bizarre patterns. We sit at the carved bar counter in the kitchen, and my son, also Boris Plaksiy, begins to remember:

"This is not just an apartment, but a workshop where he worked until his last days. If he and Horska made mosaics from glass and ceramics, then he started working with wooden forms on his own. My father could find a branch on the street and turn it into a work of art. He also involved me in the work when I was little, allowed me to carve something. Once he even took me with him on an expedition to Cherkasy region, where he created a park of giant wooden sculptures on the Shevchenko theme."

But all this was on the eve of the collapse of the USSR. Before that, Boris Plaksiy had to fully experience the KGB purges of dissidents. The persecution began after he, together with other dissidents, signed the “Letter of 139”. The consequences were not long in coming. Plaksiy was forced to independently redo the murals in the Khreshchaty Yar restaurant in the center of Kyiv, where several dozen progressive modern poets were depicted. The artist categorically refused, so the murals were scraped off the walls by builders, and he was fired from the monumental workshop of the Kyiv Art Combine.

Boris Plaksiy

"It was a wolf's ticket, because without a state order you were actually left without income. Friends tried to help my father, gave him their orders to mint portraits of Lenin, which they themselves no longer had the strength to make. He was forced to make them. In the end, he went to Siberia, where he worked as a designer. Such a forced self-exile," says Plaksy's son.

Almost ten years later, the artist was able to return to Kyiv, the dissident movement was effectively suppressed, but Plaksiy maintained ties with some friends.

"I'm a vandal, but many people like my ideas"

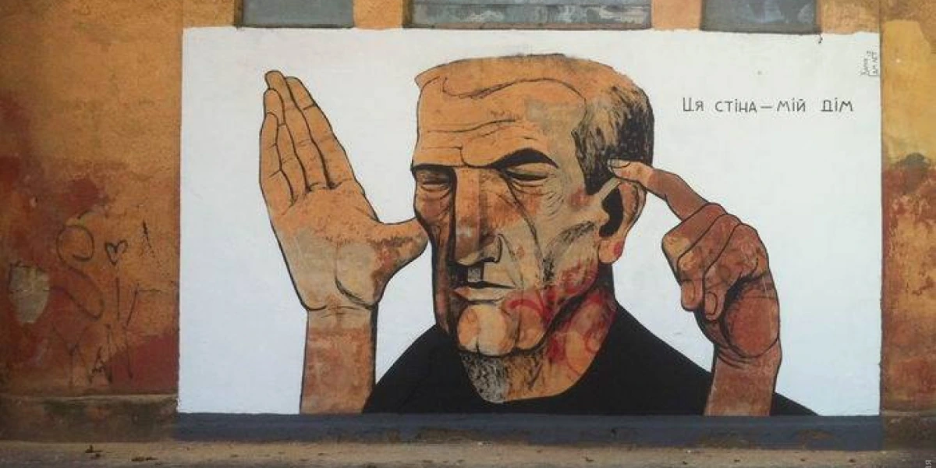

Artist Hamlet Zinkovskiy creates street art posters in black and white. For many years, city authorities equated his murals with vandalism, and utility workers destroyed works of art. However, with the beginning of a full-scale invasion, Hamlet's mural adorns the central entrance to the dilapidated city council building. This mural with symbolic explosive cocktails has not been touched. Just like his other works.

“Kharkiv is my street gallery. All the city’s residents know who the author of the works is, and in case of need, they come to their defense. I’m so happy about this! This is defending the common space. While everyone was confused, I made a bunch of works on the streets using a barbaric method. If you add up the fine for each one, it would be a fantastic amount. I’m a vandal. But many people like my ideas. In addition, I’m preparing Kharkiv for the return of people after the war.”

It is impossible not to notice Hamlet's murals, you encounter them at every step. In addition to traditional fences and walls, the artist also uses more original locations, such as transformer boxes, iron doors or garages. Each drawing of Hamlet is necessarily accompanied by his signature short captions: "Time hears us", "The keys are waiting for their owners".

Mural of Hamlet Zinkivskyi

" I don't interact with the city authorities, I don't notice them. I'm not interested in cooperating with them, although such offers have been made. I'm self-sufficient. The police don't bother me, and if they do stop me, it's to take a selfie with me. Of course, it wasn't always like that, once they would take me to the police station, but later the name started to work for us and gives us a kind of indulgence for creativity ."

If the Ukrainian monumentalists of the sixties hoped that their works would last for centuries, then contemporaries do not expect that their murals will last even ten years. They say that time has sped up. However, nonconformism has not disappeared. The unwillingness to play by the rules of the authorities continues to unite different generations of Ukrainian artists who have chosen the streets for expression. However, one should certainly distinguish between the struggle for freedom of expression in a closed totalitarian system and new challenges in a young democratic country in a state of war, where artists still have the opportunity to openly engage in dialogue with society and the bureaucracy. The "right to draw" takes a lot of nerves from modern muralists, and it often cost their predecessors their lives.

Visuals — photo by Serhiy Prokhorov, Ukrainian.Media; birdinflight.com; wikiart.org; Village.

The text was written as part of the Rozstaje scholarship.

The project is co-financed by the governments of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia through the Visegrad Grants of the International Visegrad Foundation. The foundation's mission is to promote ideas of sustainable regional cooperation in Central Europe.

The text is published with the support of partners: Stichting Global Voices, Bázis - Hungarian Literary and Artistic Association in Slovakia, Fiatal Írók Szövetsége, Czech Association of Ukrainians, College of Eastern Europe and the media "Sensor".