UNESCO has recognized Ukrainian kobzarism as a world intangible cultural heritage. The performance of historical or religious songs accompanied by a kobza or bandura dates back to the 12th-13th centuries, during the time of Kyivan Rus. In modern Ukraine, this tradition has undergone significant changes, performers have evolved along with the audience, and singing to an electric bandura is no longer surprising. However, kobzars have never been just musicians; their mission was also to preserve national identity.

"Bandura is the key to discovering your roots"

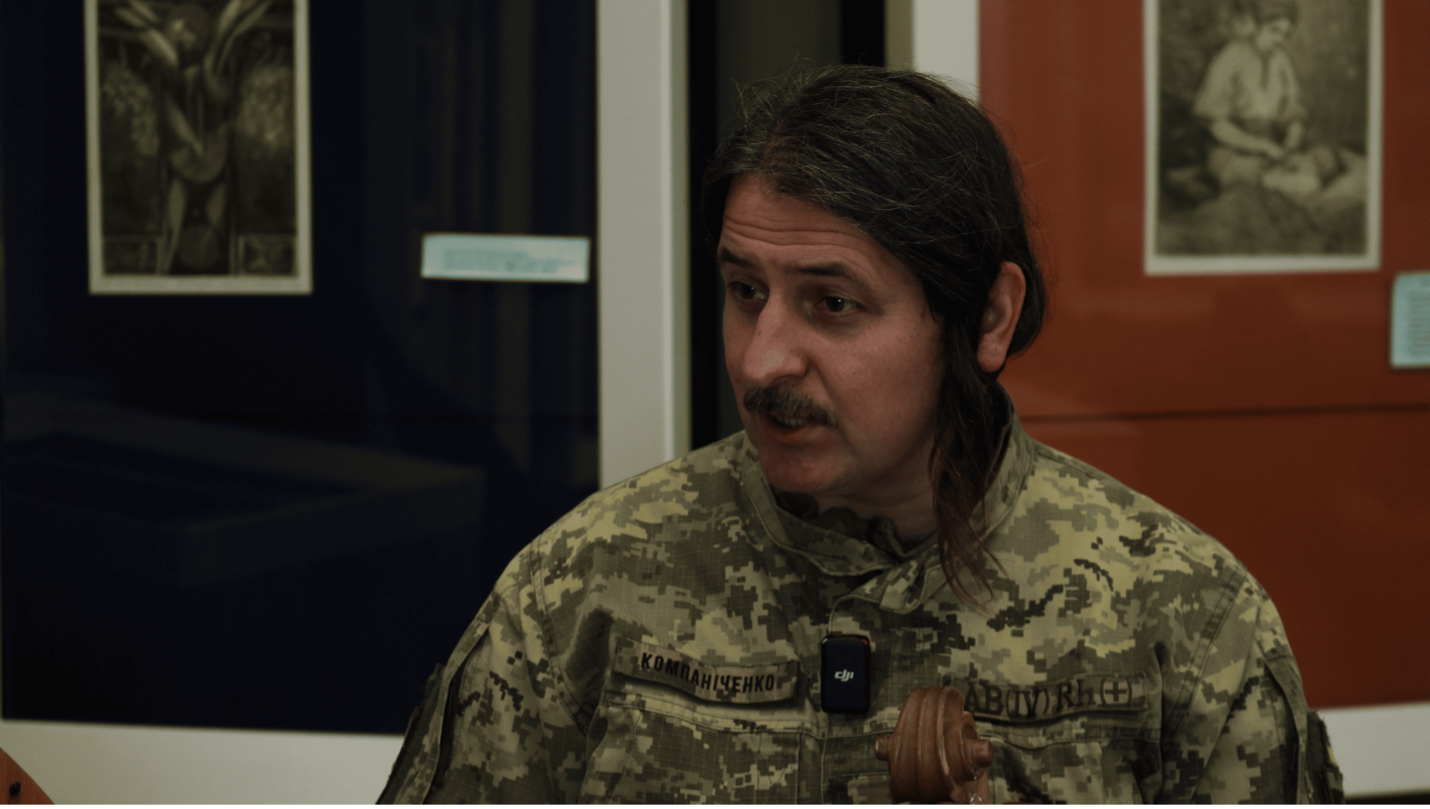

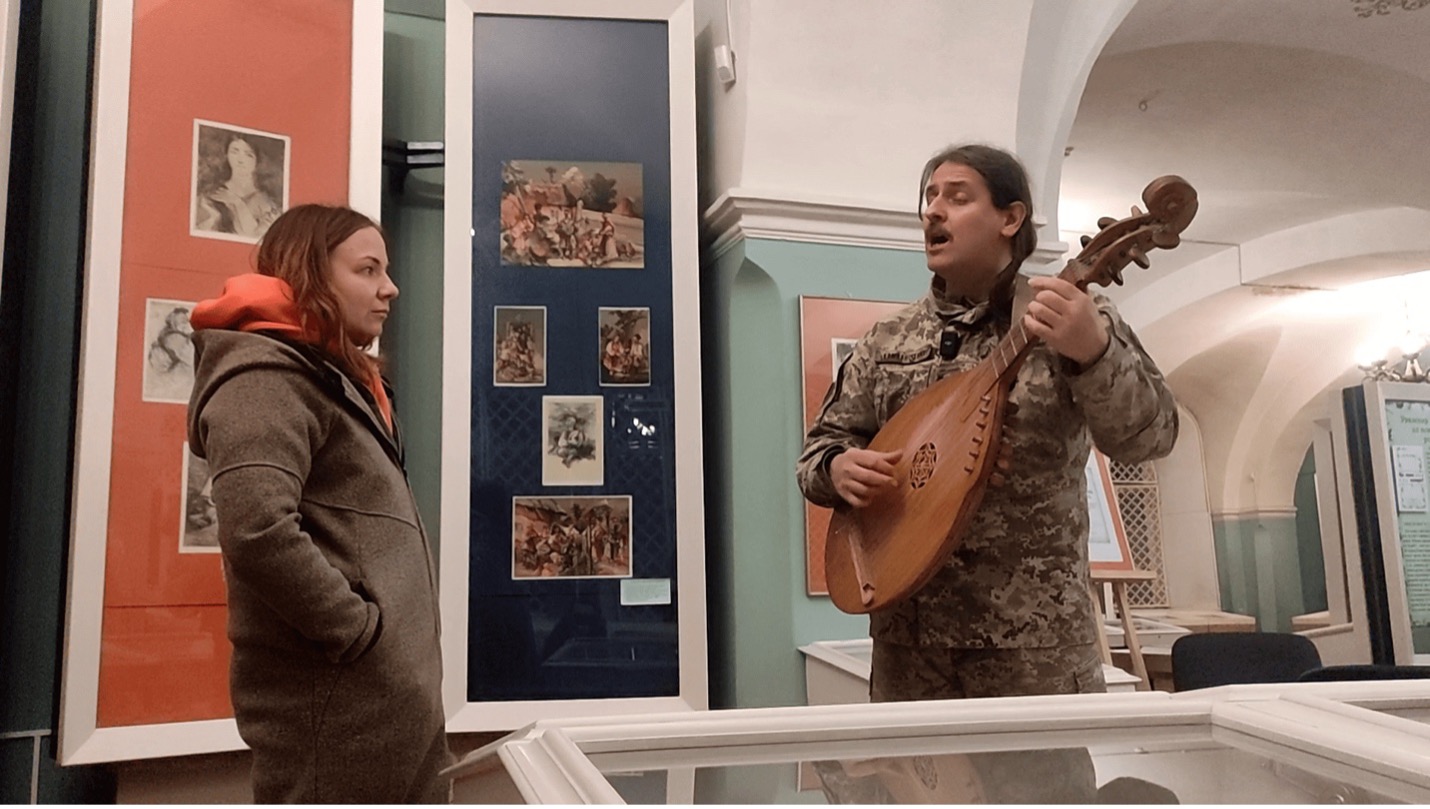

Musician Taras Kompanichenko makes an appointment at the Museum of Books and Printing. He worked there as a leading researcher. However, since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the most recognizable Ukrainian bandura player has become a sergeant in the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Now his main duties are purchasing jammers for drones and repairing transport, and performances are increasingly held at farewells to fallen soldiers. Kompanichenko, dressed in a pixel, carefully lays out three banduras on the table, each about a hundred years old.

"When I was first shown an old-world bandura, I was amazed. It was about authenticity, because it seemed that the instrument was hanging on the wall as if dead. And it turned out that it also functions, you can play it. Then I began to understand that we, bandura players, are mediums who indirectly connect generations through torn worlds."

The historical and folklore collection "Zaporozhskaya Starina" (1838) notes that in Ukraine there is a guild of bandurists who, under the guise of beggars, travel from village to village, "singing about the past to their fellow countrymen." Kompanichenko believes that in this way the songs preserved the true history of Ukraine, which the Russian colonialists repeatedly tried to rewrite.

"Kobzars sang dumas, that is, they retold heroic epics in Ukrainian, about the glorious deeds of the heroes of their native land. And the listeners were bound to feel a sense of dignity, an awareness that in the past Ukrainians were not slaves, that they were descendants of a knightly nation. This was dangerous for the Russian Empire, but it felt so confident that it allowed such freethinking."

In 1899, during the 11th archaeological congress in Kyiv, scientists decided that it was necessary to study the phenomenon of kobzarism. Appointed members of the committee searched for kobzars and recorded their repertoire. And the musician, writer and educator Hnat Khotkevych organized a large-scale concert in Kharkiv with the participation of kobzars from different provinces. Dozens of works were played by duets, quartets, and a capella, despite the fact that most of the performers were blind and conducting people who could not see was extremely difficult. The concert was a great success among the Kharkiv intelligentsia.

True, Khotkevych then came under the attention of the special services of Tsarist Russia as a person too involved in Ukrainian affairs. But real repressions awaited him ahead, under the Bolshevik regime. Like many artists after the February Revolution, Khotkevych tried to cooperate with the Soviet authorities: he organized a choir and even created a bandurist band at the Chapaev Division, which performed at the army Olympics. In the 1930s, a purge of kobzars began, it is known for certain that some of the bandurist bands of the Poltava and Kyiv bands were shot or exiled to Siberia. The same fate befell Khotkevych: the “troika” sentenced him to death, and the sentence was carried out in the basement of the Kharkiv NKVD internal prison.

"There are three forms of cultural genocide: some artists can be physically destroyed, some can be reshaped to suit their needs, and those who remain will flee on their own. Kobzarism suffered all three; the Bolsheviks destroyed kobzars because they embodied Ukrainian identity," states Taras Kompanichenko.

Some kobzars managed to emigrate during World War II, they promoted the art of bandura in the USA and Canada. Those who remained, the Bolshevik dictatorship tried to adapt to their own cultural needs. The instrument itself was not banned, but not everyone was allowed to play it. Taras Kompanichenko recalls how in childhood he was forced to perform odes to "Grandpa Lenin" to the accompaniment of the bandura.

"The communists wanted to use the authority of kobzarism, occupying this "tribune". They aimed to put the bandura as a part of Ukrainian art at the service of the needs of the Soviet state. Often this went against the task, because people could always appeal to the real one: they say, we are for proletarian values, but we want to remain Ukrainians. There was such a screen."

Thanks to his parents, Kompanichenko met dissidents, with whom he began to go on ethnographic expeditions, recording authentic songs and discovering forbidden historical facts for himself. In addition, the bandurist headed the youth branch of the Ukrainian Helsinki Union. It was then that musical and social activities finally intertwined for Kompanichenko and became a single whole. With the bandura, he attended rallies, met from exile the leader of the national resistance Lev Lukyanenko and human rights activist Ivan Kandiba.

"What did the sixties tell me? You have to take responsibility for all of Ukrainian culture, as if there was no one else but you, don't rely on anyone. They taught courage, warned: you will be scolded, you will be called out, you will be under this influence, but you must be brave to the end."

Kompanichenko was one of the lobbyists for recognizing kobzarism as an intangible cultural heritage.

"How well we are known abroad depends on how well we know ourselves. It's like connected vessels. And the bandura is the key to discovering our roots and positioning ourselves in the world."

"The bandura was like a rattlesnake to them"

Professor Kostyantyn Novytsky rushes like a whirlwind through the corridors of the National Academy of Music of Ukraine, where he teaches classical bandura. At 76, the professor is full of vital energy. All around you can hear the echo of melodies that interrupt one another - this is what students are rehearsing. In the 70s, Novytsky founded a progressive vocal-instrumental ensemble - VIA "Kobza", which was compared to The Beatles. The performers gathered full halls at home and abroad, the band's records had millions of copies.

At the beginning of their formation, the band had two problems. The first was technological: they had to create an electric bandura to modernize the sound.

"Master engineer Zarubinsky figured out how to make the necessary strings from two turns of copper wire, we magnetized them once a week. For the first time in the world, an electric bandura sounded at six in the morning, and it was my instrument! I remember it was raining, I got a little electrocuted."

The second problem was more serious — an ideological one, which appeared when the young musicians wanted to approve the name of the band.

"The party bodies calculated everything, allowed experiments up to a certain limit. For them, even the electric bandura was like a rattlesnake. And then there was the name, which was associated with kobzars, the national movement. But we were persistent, explained that we wanted to promote folk songs in a pop style of performance. And we popularized the kobza as a musical instrument. In the end, we received permission."

Novitsky sincerely says that he never felt that the Soviet system used VIA Kobza as a caricature of the “lesser brothers,” as if bandurists were poor country musicians and Ukrainian culture was not as refined as Russian. On the contrary, the musicians seized the opportunity to promote Ukrainian culture around the world.

"Our fans came up with a rhyme when we hit the charts in the US: 'Let the hippies grin with anger, / It won't drown out the bandura of Kostya.' Of course, we also visited all the cities of the Union on tour. In the Far East, our songs were sung in Ukrainian, we educated people, taught them to respect Ukrainian culture. Were there any questions about our repertoire? Of course, they asked us to perform a patriotic block. And we sang Cossack songs in it, for example, 'Oh, I'm going to the forest and I'm going to the forest.' Frankly speaking, we didn't try to secretly promote forbidden topics, we took from others and saw our task as awakening the genetic memory of Ukrainians."

Despite his caution and popularity, Novytskyi still fell under the millstone of the system: due to slanderous accusations of nationalist activities, he was banned from traveling for ten years. All of the band's foreign tours took place without his participation. In the end, the musician got tired of enduring the humiliation.

"I came to the city party organization and said, 'Good afternoon. If they don't let me out again, I'll go to Odessa, buy an air mattress, and sail to Turkey.' The problem was solved, and then it became finally clear that this was sabotage against me personally, and the ensemble was useless."

"The mission is to convey the true story"

Novitsky founded the Kobza VIA to popularize the bandura, and achieved remarkable success in this, even under the conditions of the Soviet Union. Forty years later, in free Ukraine, Yaroslav Dzhus, the leader of the Shpilyasti Kobzari group, set himself the same goal. Yaroslav did not like the fact that only folk works were performed on the bandura, because he was convinced that you can play anything on it: covers, hits, dance music, lounge, and thanks to the modern presentation, it will be easier to convince young people that the bandura is cool. Dzhus decided to promote the Shpilyasti Kobzari by participating in a talent show.

"To my surprise, we were accepted into the group as exotic. Unfortunately, fifteen years ago in Ukraine, singing in Ukrainian and playing the bandura in an embroidered shirt seemed unnatural. However, we took the opportunity to reach a mass audience and did not miss it."

"Shpilyasti Kobzars" quickly gained immense popularity, they began to be invited to corporate parties, fashion shows and even nightclubs, where bandura was previously impossible to see. The group played more than a thousand concerts in 30 countries, visiting Europe, Canada, America, Saudi Arabia, and China. Now "Shpilyasti" strives for their tracks to appear in international charts.

When I ask if he managed to captivate Ukrainian youth with his ideas, Dzhus triumphantly shows a message from a teenager who thanks the band for their creativity and says that she has started learning to play the bandura. In recent years, the instrument has become no less popular in music schools than the piano. Yaroslav Dzhus himself, having an absolute pitch, did not follow the well-trodden path of the conservatory, but graduated from a little-known kobzar college at that time. When a native of Kyiv came to the village to get a musical education, it was strange.

"Fresh air, water from a spring, lakes, you go there in the warm season and swim. I went out into the garden, picked an apple from the tree, sat under it, and played the bandura. It was great," recalls Dzhus.

He shares the opinion that the continuity of generations in the kobzar tradition is extremely important and in the pursuit of modernization and rethinking it is important not to lose the essence of the musical and social phenomenon.

"We are kobzars, but spired. I used this play on words so that conservatives wouldn't pick on us. But still, we are not just bandura players who play a piece at concerts - we convey Ukrainian values, we elevate the human spirit. We have always had an educational component. We no longer go from village to village, like ancient kobzars, but travel by car, bus, or plane. But the mission remains the same - to convey the true story."

One of the band members, Volodymyr Vikarchuk, is currently serving in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and the other "Spiky Kobzars" regularly play for the military.

"It was very impressive when we gave a concert for the Marines. There were 400 or 500 people sitting in the hall, and we heard loud applause from strong male hands, without a single whistle or scream. Or a performance for stormtroopers who had just returned from a mission, almost to zero. Everyone is tired and exhausted, it is clear that they do not need this bandura at all now. But one or two songs - and that's it, they light up. We often do interactive activities: we play a fragment of a world hit for each soldier, most often they order AC/DC Highway to Hell. After the concert, they thank us for giving us an understanding of what they are fighting for. They say that we see that the bandura is a brand of Ukraine, it must be preserved for the sake of our complex history, our people, language, and culture."

The text was written as part of the Rozstaje scholarship.

The text is published with the permission of the editorial office of the media outlet "Sensor".

The project is co-financed by the governments of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia through the Visegrad Grants of the International Visegrad Foundation. The foundation's mission is to promote ideas of sustainable regional cooperation in Central Europe.

The text is published with the support of partners: Stichting Global Voices, Bázis - Hungarian Literary and Artistic Association in Slovakia, Fiatal Írók Szövetsége, Czech Association of Ukrainians, College of Eastern Europe and the media "Sensor".